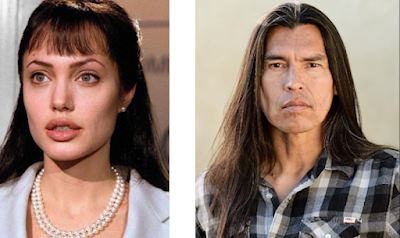

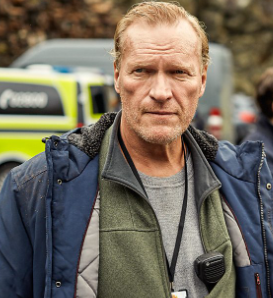

In this 11th book in the 'Inspector Konrad Sejer Mystery' series, Sejer investigates the death of a toddler. The novel can be read as a standalone.

*****

As the book opens, Norwegian Inspector Konrad Sejer is contemplating his mortality. Sejer's been having dizzy spells and losing his balance, and he's convinced he has a brain tumor. Sejer's daughter Ingrid keeps urging him to see a doctor, but the inspector is reluctant to have his fears confirmed, and makes excuses not to consult a physician.

In the midst of these dark thoughts, Sejer gets a call from his colleague, Inspector Jacob Skarre, who reports, "We've got a drowning, in Damtjern, the pond up near Granfoss....A little boy, sixteen months old. His mother found him by the small jetty, but it was too late."

Sejer gathers up his chubby dog Frank Robert, a Chinese Shar-Pei whom Sejer takes everywhere, and hurries to Damtjern.

When Sejer arrives at the pond, he sees the child, Tommy Brandt, lying on a tarpaulin. Tommy, who has the features of a Down Syndrome child, is naked, and appears to be well looked after with no visible trauma. Sejer learns the parents are a married couple: Carmen Zita and Nicolai Brandt, ages 19 and 20 respectively.

Carmen's father, whom everyone calls Pappa Zita, owns a 24-hour fast-food restaurant, and Nicolai works there while Carmen takes care of Tommy.

Once the forensics team is gone and an ambulance has taken Tommy away, Sejer interviews Carmen and Nicolai separately, as police procedure dictates.

Carmen's story goes like this:

It was a hot day, and Tommy was sweaty, so Carmen took off his clothes and let him play in the kitchen while she made lunch.

In the meantime, Nicolai was in the basement fixing bicycles, which he does for extra money.

Carmen went into the bathroom for a few minutes, and when she returned, Tommy was gone. Carmen looked around the house, then ran out into the yard, and down to the pond. She saw Tommy in the water, pulled him out, and tried to revive him, to no avail.

Carmen yelled for Nicolai, who came running, and also tried to revive Tommy, without success. Nicolai called emergency services, and the EMTs worked on Tommy for an hour, but the child was gone.

When Sejer interviews Nicolai, his story tallies with Carmen's in so far as he was fixing bikes in the basement, heard Carmen shouting, ran down to the pond....and so on.

Sejer notes that while Nicolai is distraught about Tommy drowning, Carmen is oddly distant and calm. Sejer becomes suspicious of Carmen, and when an autopsy proves she's lying, Carmen changes her story - blaming shock and confusion for the discrepancies in her tale. In any case, Carmen INSISTS Tommy's death was an accident and she did nothing wrong.

As the story proceeds we follow Sejer's investigaton as well as the actions of Carmen and Nicolai.

Sejer knows Carmen must have been disappointed to have a child with Down Syndrome, and he feels sympathy for her. Still, Sejer believes all children deserve protection and justice. Given Carmen's changing story, a hearing is scheduled while Sejer continues his inquiries.

Meanwhile, Carmen - who's always been coddled and spoiled by her father Pappa Zita - blithely gets on with her life. She gives away Tommy's things; cajoles Nicolai into going on a vacation (paid for by Pappa Zita); and insists she and Nicolai move forward....maybe have another baby.

For his part, Nicolai begins drinking heavily and smoking, and descends into the depths of despair.

In part, the story is about Down Syndrome. When prenatal tests prove a fetus has Down Syndrome, many women choose to abort. Carmen wasn't tested for fetal abnormalities, and was shocked to give birth to a 'disabled' child. Given the circumstances - and assuming Carmen hurt Tommy - would a judge and jury have sympathy for her?

By the end of the book, we know how Tommy died, and so does Inspector Sejer, thanks to his dog Frank Robert. We also learn why Sejer is having dizzy spells.

This short novel is different from previous Sejer books because it's less of a police procedural/mystery and more of a psychological analysis of the main characters. I found the story compelling and was interested to know the outcome.

Rating: 3 stars