The reputations of scientists may wax and wane, and that's part of the story told by Jason Roberts in this book. In the 18th century, Carl Linnaeus and Georges-Louis de Buffon - who were called naturalists at that time - both wanted to describe all life on Earth. That was impossible, especially in the 1700s, but both men made important contributions to biology. Soon after their deaths, Linnaeus's star brightened as Buffon's star dimmed, but that changed over time.

Linnaeus and Buffon were both born in 1707, but were complete opposites. Roberts notes, "Carl Linnaeus was a Swedish doctor with a diploma-mill medical degree and a flair for self-promotion, who trumpeted that 'nobody has been a greater botanist or zoologist' while anonymously publishing rave reviews of his own work."

Carl Linnaeus

Conversely, "Frenchman Georges-Louis de Buffon, the gentleman keeper of France's royal garden, disdained contemporary glory as 'vain and deceitful phantom', despite being far more famous than Linnaeus during his lifetime." Buffon was also more of a polymath than Linnaeus, interesting himself in probability, mathematics, and cosmology.

Georges-Louis de Buffon

Roberts' mini-biographies of Linnaeus and Buffon are informative and entertaining. This is a long book with a great deal of information so I'll just give nutshell synopses.

In brief, Linnaeus was born in Småland, to Reverend Nils Linnaeus and his wife Christina. Young Carl was fascinated by flowers, and his father taught him the names of all the plants in his personal garden. By the age of ten, Carl was supposedly studying for the ministry, but he did poorly in his classes, being much more interested in botany. Reverend Nils then decided Carl would be a doctor, and after diverse but sparse 'medical training' - often in the midst of severe poverty - Linnaeus was deemed a physician. Still, Linnaeus' main interest was plants, many of which were used for treating illnesses, which fit right into Linnaeus' pursuits.

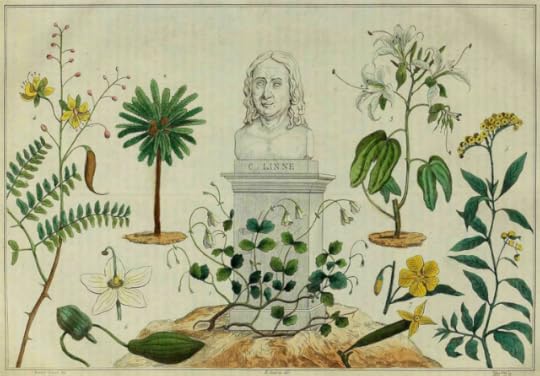

Linnaeus was interested in botany

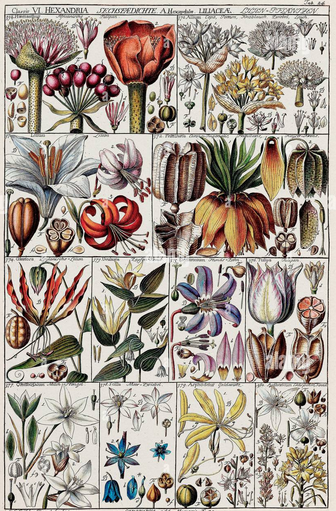

Even back in the 1700s, books describing plants' appearances and medical properties were useful for choosing the correct herbal remedies. However, the tomes were unwieldy, vague, and difficult to use. Roberts notes, "For field identification, one would either need to tote along a very large book or memorize all 698 genera." Thus Linnaeus proposed a new system of plant identification, based on the flowers' reproductive organs (pistils and stamens), which resulted in 26 categories.

18th century chart of plants

Eventually Linnaeus decided to create a master plan for all life on Earth, 'a logical arrangement that accommodated every single species.' Linnaeus was limited in his vision because he hewed closely to the story of creation in the Old Testament, which states that God made plants and trees on the second day; birds, fish and sea monsters on the fourth day; and all other organisms on the sixth day. By the seventh day, Creation was complete, and all animals and plants that would ever exist were present and accounted for. To say otherwise would be blasphemous, and Linnaeus was a true believer.

Roberts observes, "When one viewed life through this lens of fixity, it was against faith to envision new species coming into existence, or existing ones fading into extinction." Thus to Linnaeus, all life was equally related, having been created at the same time. Moreover, numerous theologians and scholars, taking the size of Noah's Ark into consideration, determined the number of animal species on Earth topped out at something over 2,000; and Linnaeus speculated that plants crested at about 23,000 species. Therefore a complete catalog of all life was doable, the only challenge being organizing it.

Rendering of Noah's Ark

Linnaeus finally declared that there are 40,000 species of living creatures, including vegetables (plants), worms, insects, amphibious animals, fishes, birds, and quadrupeds.

In time Linnaeus published the 'Systema Naturae' that introduced Linnaean taxonomy.

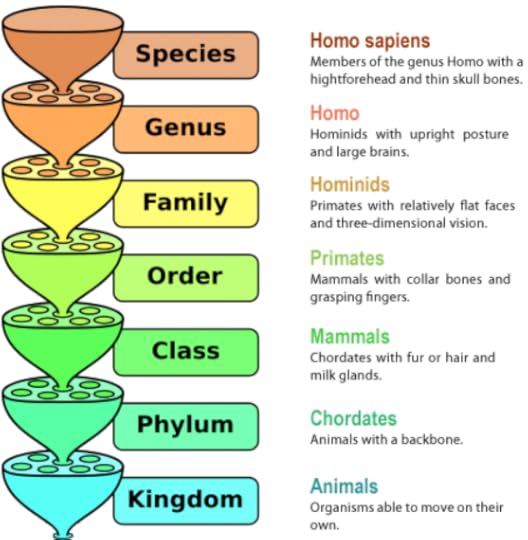

Linnaeaus' system classified organisms into three kingdoms: animal, vegetable and mineral, and ranks: kingdom, class, order, genus and species. For species names, Linnaeus introduced binomial nomenclature - the use of genus and species names. For example, Homo sapiens are humans; Canis familiaris are dogs; Felis catus are domestic cats; Quercus rubra is the northern red oak; Helianthus giganteus is the giant sunflower; etc. Scientists now use more categories than Linnaeus, but this is the basic idea.

Linnaeus clung strictly to external characteristics to construct his classes, which ended with artificial conglomerations of organisms. For Kingdom Animalia, Linnaeus designated six 'real' classes and a 'false' one:

♦ Quadrupedia: four-footed animals, mostly mammals

♦ Aves: birds

♦ Amphibia: frogs, toads, salamanders, alligators, crocodiles, walruses, beavers

♦ Pisces: fish, whales, dolphins, seacows, narwhals

♦ Insecta: insects, scorpions, aquatic crabs

♦ Vermes: this was a 'wastebasket category' containing reptiles, mollusks, sponges, squids, earthworms, and more

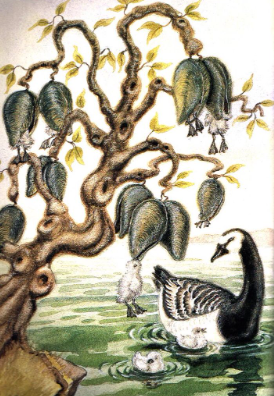

♦ Paradoxa: fake organisms like the barnacle tree, unicorn, satyr, phoenix, hydra

Mythical Barnacle Tree

In time Linnaeus became a professor at Uppsala University, lecturing on topics related to medicine and botany. Then to expand the 'Systema Naturae', Linnaeus started his apostle program in 1746. "Over the next three decades he would anoint fourteen of his students as apostles, sending them out on quests to gather specimens around the globe." Each apostle was given a wish list, and 34-year-old Christopher Tarnston was sent to China and asked to gather things like: a tea bush; seeds for the Chinese mulberry tree; fish; plants with flowers and fruit; insects; snakes; drugs; and more. Most of the apostles failed in their missions, and many died along the way.

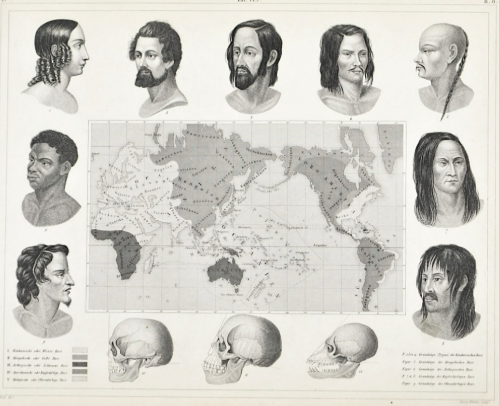

Though Linnaeus did much that's praiseworthy, he's also been dubbed the father of racism for sorting humanity into the following vague unspecified categories:

Homo sapiens europaeus (White European): Fair, yellow hair, blue eyes, gentle, acute, inventive; governed by laws.

Homo sapiens americanus (Red American): red-colored, hot-tempered, black hair, face harsh, beard scanty, stubborn, cheerful, paints himself with red lines.

Homo sapiens asiaticus (Tawny Asian): sallow, melancholic, strict, dark hair, dark eyes, severe, haughty, greedy, governed by opinions.

Homo sapiens afer (Black African): black contorted hair, silken skin, snub nose, swollen lips, women expose their breasts, sly, slow, careless, anoints self thickly. governed by whim.

Roberts writes, "Defining one group as 'governed by laws' and another as 'governed by whim' could not be a more blatant assertion of superiority"....and Linnaeus stood by his categories for the rest of his life.

Linnaeus was also something of a misogynist, and he deemed his four daughters unworthy of education, and only allowed them to learn domestic skills. (This is a big no-no in my book. 😠)

Linnaeus has been revered for his contributions to science, but his reputation has dimmed in the long run.

*****

Georges-Louis de Buffon was born in the village of Montbard and lucked into inheriting a huge fortune from his mother's aunt and uncle. Buffon was well-educated, and once he'd sowed some wild oats, Buffon built a regal home in Montbard and established the Parc Buffon, where he began tree-growing experiments.

Parc Buffon

At age 27, Buffon was appointed administrator of the Jardin du Roi in Paris, which became one of the best scientific institutions in Europe.

Le Jardin du Roi

Savants and amateur naturalists around the world sent seeds, samples, and curiosities to the Jardin, and Buffon took it upon himself to reorganize and catalogue much of the collection, which had been accumulating for decades but never appropriately curated. To obtain a framework for his organization, Buffon read Linneaus' 'Systema Naturae' and immediately took issue with it.

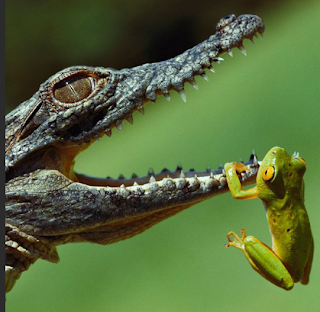

For Linnaeus, nature is divided into distinct parts, which he organized in his taxonomic system. Buffon disagreed, believing classification is conditional, and nature isn't divided into well-defined groups. In short, while species might be real things, the hierarchical groupings of genera and beyond should be approached with caution. (This seems obvious enough, since Linnaeus grouped frogs with alligators, and fish with dolphins.)

Frog and Alligator

Fish and Dolphin

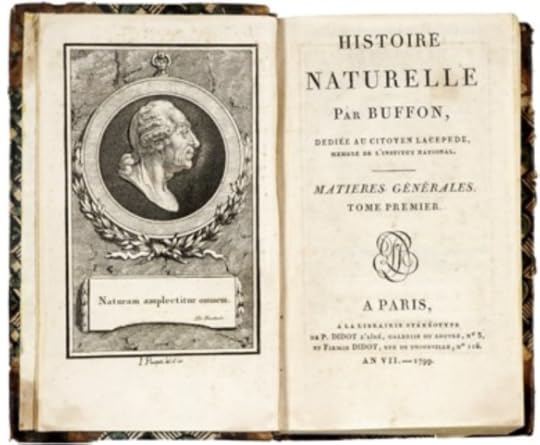

Buffon spent much of his life writing his 'Histoire Naturelle', which would be "a grand tour of all the objects presented us by the Universe" in 36 volumes.

Buffon devoted the first and second volumes to present his theory of the Earth's formation and development. Buffon stated that the Earth was not created as the singular act described in the Bible, but that the planets had slowly accumulated from molten matter ejected from the sun. Buffon also asserted that the sun will die out, and the Earth and other planets will become extinct.

Buffon went on to write about Homo sapiens and then animals, etc. Buffon's plan, with the help of his protege Michel Adanson, was to devise a means of organizing life that avoided Linnaeus' error of over-simplicity, but "to place together those things that resemble one another and separate those which differ." Buffon disagreed with Linnaeus about the number of species on Earth, believing there were much more than 40,000 species AND that the planet's history had even more organisms, but many had gone extinct.

Biodiversity

Buffon's work implied extinction and evolution (though he didn't use that word), which sent the Christian establishment into an uproar. The 'Ecclesiastical News' rumbled about the book injuring God and damaging the faith, and critics urged Buffon to renounce his heresy. In future printings, Buffon was forced to include language disavowing his heretical statements, but he did not change or remove a single word of what had been published....later saying "It is better to be humble than to be hung." In subsequent volumes, Buffon included passages carefully crafted to deflect religious censure.

With regard to humans, Buffon disagreed with Linneaus' four categories, and considered it repugnant to affix attributes like 'severe, haughty, greedy' to Asian people and 'sly, slow, and careless' to Black Africans.

Buffon's work was disparaged after his death, but later came back into vogue, especially when Charles Darwin (b. 1809), author of 'On the Origin of Species' acknowledged that Buffon's 'evolution theories' preceded his own.

*****

There's much more in the book, about Linnaeus and Buffon and the people in their orbit. Then, towards the end of the book, Roberts goes on to mention other scientists who contributed to our knowledge of the world, such as Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (b.1744) - who advocated for evolution by natural selection (though he believed in the inheritance of acquired characteristics); Étienne Geoffrey Saint-Hilaire (b.1772) - who studied comparative anatomy; Georges Cuvier (b. 1769) - who's called the founding father of paleontology; Charles Darwin (b. 1809) - who proposed the theory of evolution; and more. Rogers also addresses the disruptive effect of the French Revolution on science in France, when research facilities were dismantled.

Charles Darwin

This is an excellent book for readers interested in the history of biology, and in taxonomy - the manner in which we categorize organisms. The book contains Suggestions for Further Reading, Notes and Sources, and an Index.

Highly recommended.

Rating: 5 stars

No comments:

Post a Comment