Author Yuval Noah Harari is an Israeli historian, philosopher, and author. In Sapiens, Harari presents a narrative of humanity's birth, evolution, and possible future, and it's a fascinating - but not a pretty - picture. Harari has done his research, and the book is packed with information. That said, I'll try to provide a nutshell overview.

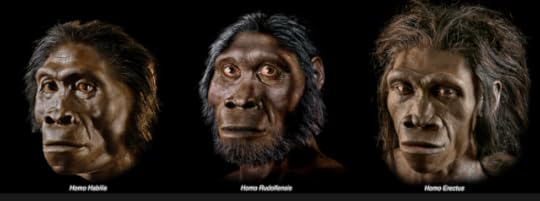

Harari starts with the creation of the universe - the 'Big Bang' 13.8 billion years ago - and quickly covers the formation of planet Earth and the appearance and diversification of life. By 2.5 million years ago the genus Homo (humans) evolved in Africa and began to spread to other landmasses. There were many species of Homo, including Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis, and others.

From left to right: Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, Homo erectus

Scientist's recreation of a Neanderthal woman

In time our species, Homo sapiens, appeared, and either wiped out or interbred with other extant humans. In any case, Homo sapiens are the only humans alive today, and Harari notes, "We imagine that we are the epitome of creation." This helps explain our selfish behavior towards the planet and other life.

Going back to prehistoric times, Harari observes that early humans "were insignificant animals with no more impact on their environment than gorillas, fireflies, or jellyfish." Four major events led to the escalation of the human race: the Cognitive Revolution, the Agricultural Revolution, the Scientific Revolution, and the Industrial Revolution.

➤ The Cognitive Revolution: The appearance of new ways of thinking and communicating, between 70,000 and 30,000 years ago, constitutes the Cognitive Revolution. Historians speculate that genetic mutations that tweaked the brain allowed Homo sapiens to think in novel ways and to use new types of language. This led to sharing information about the world and spreading gossip about people - For example: Bison are in the next valley; Brak is a good hunter; Thra has a bad temper. It also gave rise to imagination and storytelling, which brought about legends, myths, gods, and religions.

➤ The Agricultural Revolution: Humans were hunter-gatherers for millennia prior to the Agricultural Revolution - when people learned to farm - about 12,000 years ago. Growing crops, which requires digging, planting, watering, weeding, harvesting, storage, etc., is much more difficult than foraging. For this reason, historians speculate that "a series of trivial decisions....had the cumulative effect of forcing ancient foragers to spend their days carrying water buckets under a scorching sun."

Agricultural Revolution

Archaeologists point to a site in Turkey called Göbekli Tepe, where monumental pillared structures decorated with spectacular carvings were unearthed. Evidence demonstrates these were built by hunter-gatherers at the same time wheat was domesticated in the area. Thus researchers suggest "that foragers switched from gathering wheat to intense wheat cultivation, not to increase their normal food supply, but rather to support the building and running of a temple."

Example of columns at Göbekli Tepe

During the agricultural revolution, farming came to be associated with animals like sheep, goats, pigs, chickens, cattle, and so on. These creatures supplied food, raw materials (skins, wool), and muscle power. Sadly, domestic animals are among the most miserable creatures that ever lived. Harari observes, "The domestication of animals was founded on a series of brutal practices that only became crueler with the passing of the centuries....Egg-laying hens, dairy cows, and draft animals are sometimes allowed to live for many years, but the price is subjugation to a way of life completely alien to their urges and desires."

Chickens are crowded together in uncomfortably close quarters

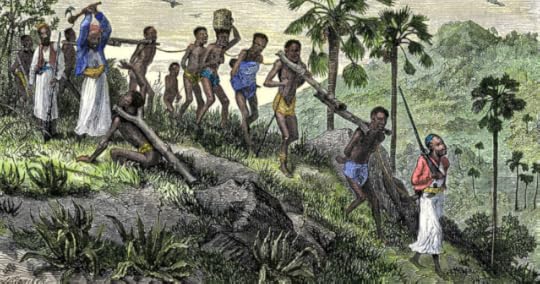

Hurari also addresses the connection between the agricultural revolution and slavery, and writes about the use of slaves throughout history. As always, enslaving and demeaning fellow humans demonstrates deplorable cruelty and exploitation.

A woodcut from 1888 depicts a slave caravan in the Congo

➤ The Scientific Revolution: Beginning around 1500 CE governments/rulers began putting resources into science - obtaining new knowledge in order to acquire new powers, and in particular to develop new technologies. Advances in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology and chemistry replaced "pre-modern traditions of knowledge such as Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, and Confucianism, which asserted that everything that is important to know about the world is already known."

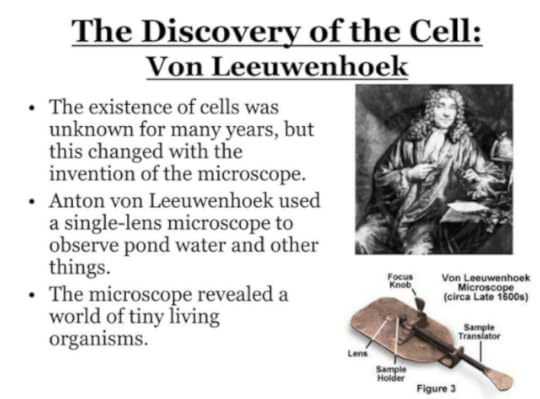

Copernicus argued that the sun, rather than the Earth, is at the center of the universe; Isaac Newton presented a theory of motion and gravitation that explained the movements of all bodies in the cosmos; Charles Darwin developed his theory of evolution; Antonie Von Leeuwenhoek's homemade microscope showed him a world of tiny creatures in a drop of water; and so on.

Scientific research resulted in the discovery of electricity; the development of deadlier weapons; advances in medicine; reduction in child mortality; etc.

Science doesn't advance in a vacuum, but is fueled by a combination of political, economic, and/or religious interests. Hurari posits the following (theoretical) example: Professor Slughorn wants to study a disease that affects the udders of cows while Professor Sprout wants to study whether cows suffer mentally when they're separated from their calves. Professor Slughorn's study is more likely to be funded "because the dairy industry, which stands to benefit from the research, has more political and economic clout than the animal-rights lobby."

Throughout history, the quest to conquer, gain riches, and acquire scientific knowledge came with consequences. Hurari notes, "In the 18th and 19th centuries, almost every important military expedition that left Europe for distant lands had on board scientists who set out....to make scientific discoveries." On the upside, humanity garnered information about linguistics, botany, geography, history, archaeology, anthropology, biology, mineralogy, etc. from all over the world.

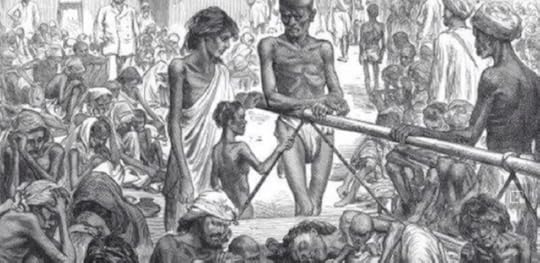

On the downside, native populations often suffered. Hurari provides MANY MANY examples of this. For instance, the British conquered Bengal, the richest province of India, in 1764. Hurari writes, "The new rulers were interested in little except enriching themselves. They adopted a disastrous economic policy that a few years later led to the outbreak of the Great Bengal Famine....about 10 million Bengalis, a third of the province's population, died in the calamity."

The Great Bengal Famine

Moreover, biologists, anthropologists, and even linguists provided 'scientific proof' that Europeans are superior to all other races, justifying the western conquest of the world....and fostering racism.

From here, Hurari launches into an EXTENSIVE discussion of economics, observing that "Money has been essential both for building empires and for promoting science.....and whole volumes have been written about how money founded states and ruined them, opened new horizons and enslaved millions, moved the wheels of industry and drove hundreds of species into extinction" All this is in the service of 'growth', and I'd suggest you read the book to learn more.

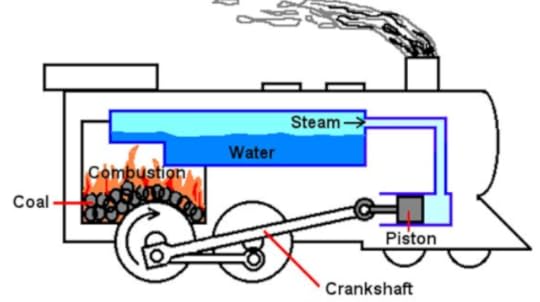

➤ The Industrial Revolution: The Industrial Revolution of the 1700s and 1800s transformed the world economy by fostering new inventions and manufacturing processes. The Industrial Revolution began with the steam engine, which burned coal to heat water, resulting in steam that initiated movement.

Steam Engine

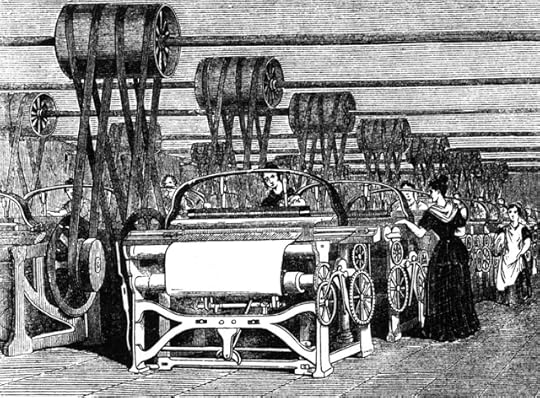

The steam engine was first used in Britain to pump water out of mineshafts. Steam engines were then used to power looms, cotton gins, locomotives, and other machines.

Power Loom

Afterwards, "people became obsessed with the idea that machines and engines could be used to convert one type of energy into another." In time, energy conversion gave us the internal combustion engine that powers cars and trucks; and electricity that we use to turn on lights, print books, sew clothes, refrigerate food, cook meals, take photos, and so on. More recently, nuclear energy has been harnessed, and atomic energy has been used to explodes bombs.

Hurari writes, "At heart, the Industrial Revolution has been a revolution in energy conversion....Every few decades we discover a new energy source, so that the sum total of energy at our disposal just keeps growing. We just need the knowledge necessary to harness it and convert it to our needs." Conventional energy sources include things like fossil fuels, the sun, wind, waves, biomass, and more.

Wind Energy

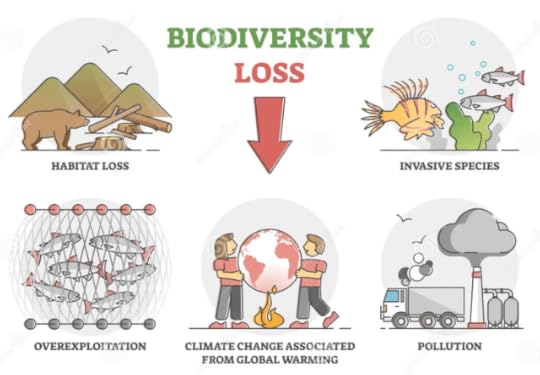

Harari goes on to demonstrate (at length) that industrialization has made the world a darker place. For example, the food industry is terribly cruel to pigs, chickens, cattle, and other 'food animals'. In addition, humans have cut down forests, drained swamps, damned rivers, flooded plains, laid down hundreds of thousands of miles of railroad tracks, and built huge metropolises - all of which destroyed habitats and wiped out species (en masse).

Hurari proceeds to write about all manner of human activities, and posits that industrialization led to the collapse of the family and community. Hurari even suggests humanity isn't 'happier' despite all the progress we've made. The author gets rather philosophical here, and once again, I'd urge interested people to read the book.

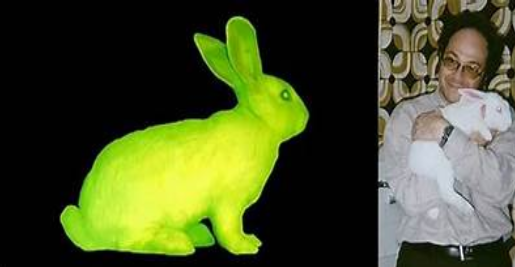

Towards the end of the narrative, Hurari includes a thought-provoking section about the future of Homo sapiens. The author contends that humans are breaking the laws of natural selection by engineering living beings in laboratories. As an illustration, Brazilian bio-artist Eduardo Kac created a fluorescent green rabbit - which he named Alba - by taking a white rabbit embryo and implanting DNA from a green fluorescent jellyfish.

Eduaro Kac created a green fluorescent rabbit called Alba

Alba is not the result of natural selection but rather the product of intelligent design - the intelligent designer being Homo sapiens. Hurari asserts, "Biological engineering is deliberate human intervention on the biological level (e.g. implanting a gene) aimed at modifying an organism's shape, capabilities, needs or desires, in order to realize some preconceived cultural idea." A bizarre example is a mouse with an 'ear' made of cattle cartilage cells.

Hurari observes that the replacement of natural selection by intelligent design could happen in one of three ways: "Through biological engineering, cyborg engineering (beings that combine organic and non-organic parts), or the engineering of inorganic life (e.g. AIs).

In Hurari's view, playing with the genes of humans could bring down the curtain on Homo Sapiens. He writes, "Tinkering with our genes won't necessarily kill us. But we might fiddle with Homo sapiens to such an extent that we would no longer be Homo sapiens." Humans might even become 'cyborgs' that combine organic and inorganic parts. Of course some people already have bionic parts, like arms or legs, but who knows how far this might go.

Bionic Arm

To sum up, this is a fascinating treatise on humanity. Lamentably, the narrative doesn't paint Homo sapiens in an especially positive light. Though there are lots of 'nice people' out there, history seems to demonstrate that humans are happy to exploit 'weak' (or naive) populations and are willing to ravish the planet - all of which is disgraceful. It also occurs to me that other life in the universe - if they're peaceful - should probably hope we don't find them.

The book is well-written and chock full of interesting information and opinions. Highly recommended.

Rating: 5 stars

No comments:

Post a Comment