Author Philipp Schott is a semi-retired veterinarian who has operated a small animal practice in Winnipeg, Canada since 1990. Schott is also the author of several non-fiction books, 'The Willow Wren', and the 'Dr. Bannerman vet' mystery series.

Author Philipp Schott

'Heal the Beasts' is a non-fiction book about the history of veterinary medicine, and though Schott is not a professional historian, he writes, "I have a passion for history, a passion for veterinary medicine, and a passion for storytelling." Schott notes this is not a textbook, but rather an idiosyncratic telling of veterinary medicine's stories across history.

At 232 pages, the book provides a brief glimpse of the slow advancement of veterinary practices over the millennia. Schott begins many chapters with a fictional veterinary anecdote related to the era, which adds a nice fanciful touch.

*****

Historically, animals were mostly valued for their usefulness to people - as beasts of burden; for protection; for hunting; to ride to battle; for meat, etc. As an example, when 12,000 horses died in one day at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, the concern was more about the expense of losing so many equines - and the difficulty of replacing them - than about the suffering of the unfortunate creatures.

The Battle of Waterloo

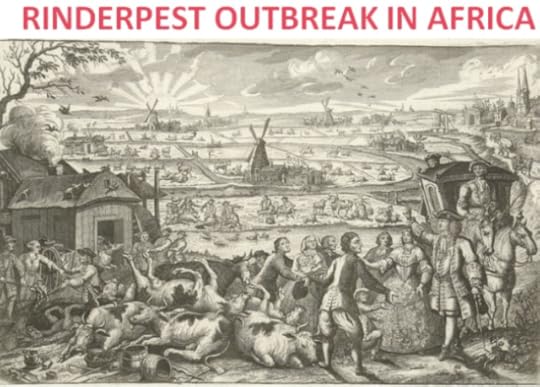

Another example is the rinderpest disease that devastates cattle, which was known as far back as ancient Egypt. When rinderpest wiped out herds of cattle in medieval Europe, people starved.

Depiction of a rinderpest epidemic

Financial losses related to sick and dying beasts resulted in the emergence of 'animal practitioners' of every stripe, many of whom were not helpful. For instance, Anthony FitzHerbert's 'Boke of Husbandry', written in the 1500s, recommends a poultice of 'feitergrasse' for chronic respiratory disease in cows.

Anthony FitzHerbert's Boke of Husbandry (which has all kinds of advice)

The nascent veterinary profession wasn't born in the middle ages however. Healers have been around since ancient times, when 'shamans' used plants and other natural substances to make potions and pastes for ailing people. Schott cites an instance of yarrow and chamomile being found on the tooth of a Neanderthal woman with a dental abscess. Such medicines were used for animals as well, especially creatures important to the group.

Paleolithic man with his hunting dog

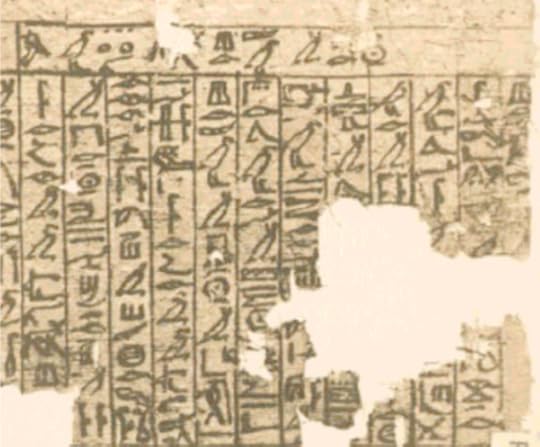

In ancient China, both acupuncture and herbal remedies were being used for animals by 2000 BCE; in ancient Egypt, texts called the Kahum Papyri, written around 1900 BCE, listed treatments for cattle, dogs, cats, birds, and fish; in ancient India, a text called the Hastyayurveda, written around 1800 BCE, described elephant diseases and their treatment; and Vegetius of the Roman Empire fashioned remedies for lame horses in the late 300s CE.

Section of the veterinary papyrus of the Kahun Papyri

Schott cites a long string of early veterinary practitioners from around the world, most of whose treatments and surgeries were ineffective. In large part, this stemmed from lack of knowledge of animal anatomy and physiology. As an example, Aristotle (284-322 BCE) was an assiduous dissector, and when he couldn't find gonads in eels, the sage declared eels couldn't reproduce, and arose spontaneously out of mud.

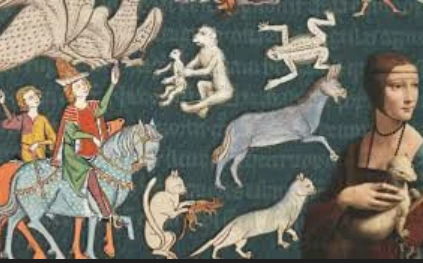

Moving on to medieval Europe, animal practitioners used an array of often futile treatments, such as herbs, holy water, blood-sucking leeches, talismans, amulets, magical coins, charmed stones, incantations, live frogs pushed down the throat, live cats rubbed across the back, and more. A tome called the Leechbook (leech means doctor) even laid out a treatment for livestock bloat caused by elves. Schott notes, "I could fill this entire book with the weird and wondrous ways of the medieval cow-leech, horse-leech, and dog-leech."

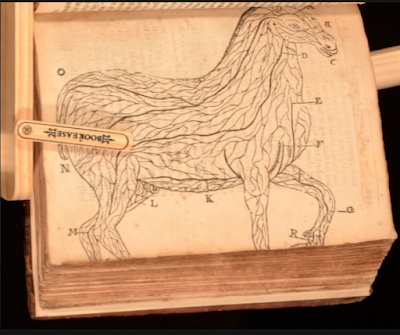

Markham's Maister-Peece Containing All Knowledge Belonging to the Smith, Farrier, or Horse-Leech, Touching the Curing of All Diseases in Horses

Practitioner in the Middle Ages drenching a horse (pouring medicine dissolved in water down the horse's throat)

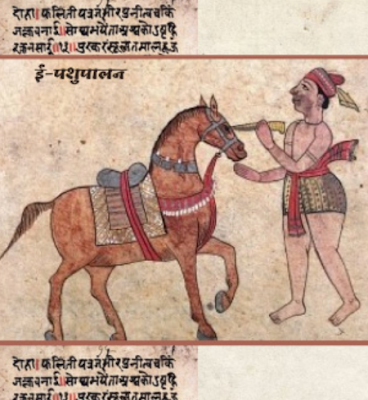

Old-time animal doctors didn't limit themselves to providing external treatments and pouring potions down animals' throats. Some early veterinarians performed surgeries - without anesthetics - and Schott describes several operations in detail, advising, "Don't try this at home."

An eye operation on a horse in India

Schott notes, "The bottom line in all the foregoing was that the European Middle Ages, as in the ancient world that preceded it, saw very progress in medicine, whether human or veterinary, though not for lack of trying...Animals were extremely valuable...A single cow could represent most of a peasant's wealth...Every effort would have been made to keep these animals in good health and treat their afflictions, but the knowledge was simply lacking." Until the 18th century, veterinary medicine was a "potpourri of theories and remedies largely based on superstition, tradition, and anecdotal observation...which did more harm than good."

Medieval Magic Veterinarian

However, in the 1700s, objective science was starting to emerge, and Claude Bourgelet (1712 - 1779) is often cited as the 'Father of Veterinary Medicine.' Bourgelet created the world's first two veterinary schools in France, and there were soon veterinary schools all over Europe. These institutions taught things like anatomy, physiology, general medicine, medicinal plants, splinting, and bandaging.

L'Ecole vétérinaire de Lyon - the world's first veterinary school

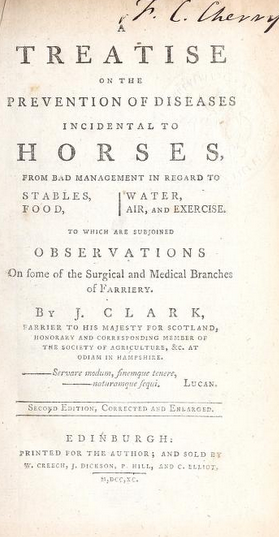

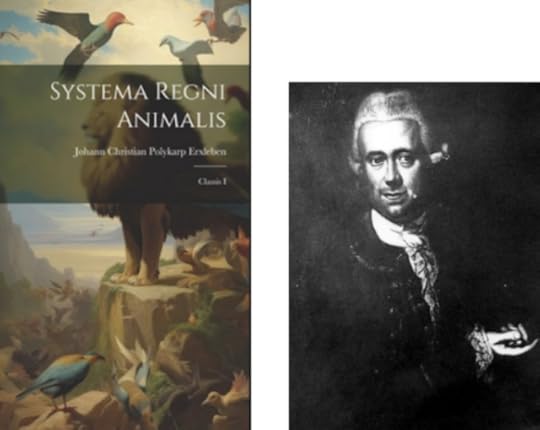

Schott proceeds to discuss 'heroes' who helped advance veterinary medicine, citing James Clark -a Scottish farrier who penned several treatises used as textbooks in the late 1700s; and Johann Christian Polycarp Erxleben - who founded Germany's first veterinary college in 1770, and emphasized scientific principles and hands-on practice for students.

Treatise on horses by James Clark

Johann Christian Polycarp Erxleben and one of his veterinary books

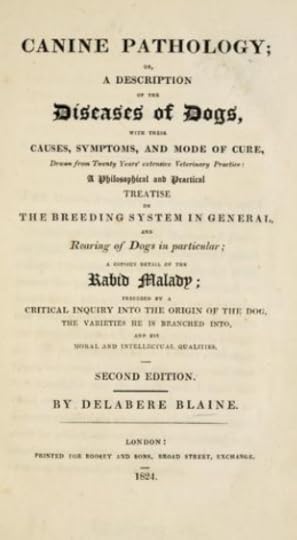

By the 19th century, veterinary medicine was advancing more rapidly, and starting to focus on 'pets' as well as economically important creatures like horses and cattle. This is evidenced by veterinarians like Delamere Blaine, who called himself 'the very father of canine medicine.' Delamere published several books about diseases and treatments for canines, and opened one of the first small animal clinics in the world.

Book about dog medicine by Delamere Blaine, published in the 1817

Advancement in veterinary science includes things like: anesthetics (1847) - which makes surgery easier; rabies vaccine (1885) - which protects dogs from the deadly disease; antibiotics (1928) - used to treat infections; etc. As a generalization, Schott lauds the expansion of basic care for animals worldwide, with many more vaccines; many more simple, humane procedures; and many more effective and affordable medicines.

A dog getting a rabies shot

Schott observes that veterinary medicine underwent its greatest crisis in the 20th century. In 1911, veterinarian' was a fancy synonym for 'horse doctor.' Though veterinarians did treat other species, especially food animals (cows, pigs, lambs, sheep, chickens, etc.) - and to a lesser extent, dogs - most veterinarians dealt with equines. Then cars were invented, and veterinarians were flummoxed. Veterinary schools closed and doom was predicted!

Of course this didn't happen because veterinarians largely morphed into pet doctors, treating dogs and cats with miscellaneous other species thrown in. (Note: I once took my parakeet to the emergency night clinic.)

A parakeet visiting the veterinarian

Over the course of the narrative, Schott gives credit to many people who had an impact on the veterinary profession. He also singles out some 'special mentions', including:

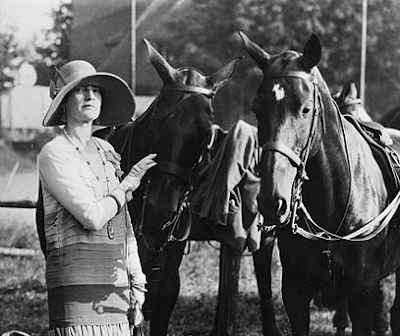

Dr. Belle Bruce Reid (b. 1883) - an Australian who became the first woman in the world to officially register as a veterinarian;

Dr. Belle Bruce Reid

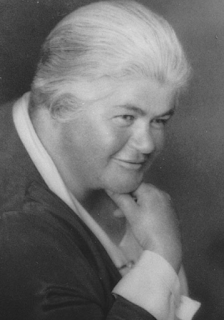

Dr. Luis Camuti (b. 1893) - the first veterinarian to specialize in cats;

Dr. Luis Camuti and his book

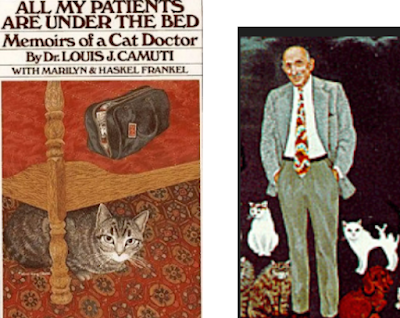

Countess Maria Helene von Maltzan (b. 1909) - a Polish veterinarian who helped smuggle Jews out of Germany during WWII;

Countess Maria Helene von Maltzan

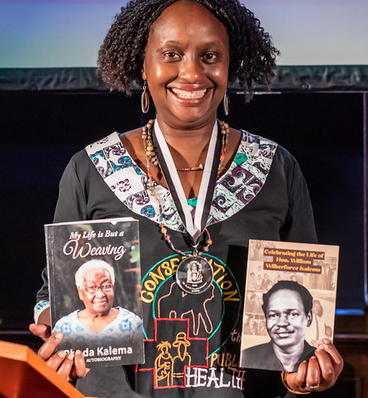

Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka (b. 1970) - an African wildlife veterinarian who treats gorillas;

Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka

Alf Wight (b. 1916), also known as James Herriot, who's famous for his All Creatures Great and Small books and the television series of the same name.

Alf Wight (aka James Herriot)

Though not all-encompassing, the book is a fascinating peek at the history of veterinary medicine, with great pictures to illustrate the narrative. My major quibble would be that some sections skip around in time, but Schott usually has a reason tor tackling subjects out of order. Highly recommended.

Thanks to Netgalley, Philipp Schott, and ECW Press for a copy of the book.

Rating: 4 stars

No comments:

Post a Comment