Yossi Yovel, an ecologist and neurobiologist, is a professor at Tel-Aviv University. Yovel has been studying bats for decades, and shares his research - and that of other bat scientists - in this book. Lest you fear this is a dry science tome, it's not. Yovel peppers the narrative with lots of engaging anecdotes, and he has a great sense of humor.

Author Yossi Yovel

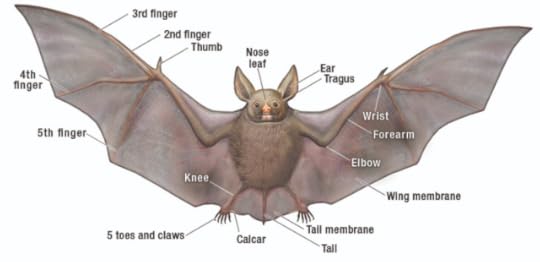

Background: Bats are the only mammals who can truly fly, their wings being a pair of hands with five extremely long fingers and a flexible skin membrane stretched between them.

The Earth harbors more than 1,500 species of bats, which range in size from the tiny bumblebee bat to the giant golden-crowned flying fox, and bats can be found everywhere, from the hottest deserts to the Arctic Circle.

Bumblebee Bat (top) and Giant Golden-Crowned Flying Fox (bottom)

Some bats live in colonies, and others live alone. Some bats are insect eaters; some dine on fruits; some consume vertebrates like fish, frogs, birds, and other bats; and a few drink blood.

A fruit-eating bat

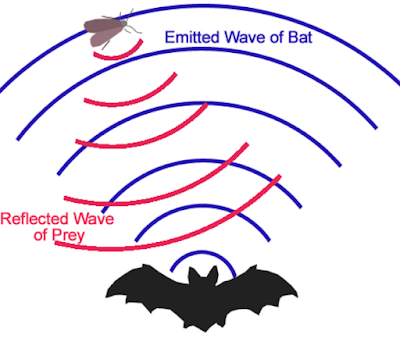

Bats are NOT blind, but since they hunt at night, most use echolocation (sonar) to find food and to avoid bumping into things. Bats can fly many miles each night to search for food, and some travel thousands of miles during migration.

Bat Swarm Migrating

Bats have good immune systems and are among the longest-living mammals. However, human activity has endangered many species, which is VERY unfortunate from an ecological perspective. Bats eat agricultural pests; consume mosquitoes; disseminate seeds of fruits; and pollinate plants, including the agave from which tequila is made.

(No agave = No tequila).

Tequila bats pollinate agave plants

Though bats are so widespread, they remain mysterious to most people. In this book Yovel sets out to reveal the world of bats from the perspective of scientists. The narrative is divided into four broad sections: sociality, echolocation, evolution, and nature conservation.

I'll provide a brief example for each topic, and would urge interested readers to read the book.

╰┈➤ Sociality

Gerald Wilkinson was interested in studying animal sociality. When Wilkinson learned vampire bats sometimes feed other adult bats, he knew the big question was: Why would one animal help another animal?

In the 1970s-1980s, Wilkinson and a research assistant used night-vision devices to watch colonies of the common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) in Costa Rica. The researchers often lay on their backs peering up into hollow tree trunks to observe the bats.

Common Vampire Bat

To feed, Desmodus crawls across the body of its prey to find a blood vessel close to the skin. The bat then injects saliva containing an anticoagulant, and drinks the animal's blood. Upon returning to the colony, mother bats feed their pups, but do they feed other adults?

Vampires have very high metabolism, and a bat that doesn't find food for three nights in a row may die of starvation. Thus food shared by a group member could save a life.

After observing vampire bats for more than 400 hours over three years, Wilkinson and his assistant documented many cases of mutual feeding, both among 'relatives' and 'bunk buddies' (bats that regularly slept close together).

Vampire bats sharing food

Moreover, a female vampire was more likely to give blood to a fellow vampire who previously gave her blood, a phenomenon called 'reciprocal altruism.' Yovel notes, "Even today, forty years later, vampire bats are considered the best-known example of reciprocal altruism."

Fun anecdote: Scientist Jack Bradbury studied bats in their natural habitat and saw unfamiliar social behaviors. Recalling observations of greater spear-nosed bats (Phyllostomus hastatus) in Trinidad, Bradbury wrote: "Every time we visited [their cave], one male would leave his group and urinate on us." Bradbury theorized that the bats lived in a harem: a single dominant male and a group of females.

Greater Spear-Nosed Bat

╰┈➤ Echolocation

In the 1940s, Donald Griffin showed that bats emit ultrasonic sounds to navigate in complete darkness. Griffin called this bat sense 'echolocation.' Three decades later, a German student called Hans-Ulrich Schnitzler became interested in greater horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum).

Greater Horseshoe Bat

Horseshoe bats use their horseshoe-shaped nose to direct the sound beam they emit from their nostrils. That is, these bats in effect "see" with their nostrils. Yovel observes, "The distance between their nostrils creates a narrow sound beam with a longer range, a sort of precise spotlight of sound....This precise frequency enables the bats to detect even the slightest movements of prey, such as the flutter of a moth's wing." In effect, bats use the Doppler effect to zero in on their prey.

Schnitzler went on to show he could use the Doppler effect to measure the bat's speed. Using food, Schnitzler trained bats to fly toward a microphone across the room. Schnitzler recorded the sound, and found that the frequency correlated with the flight speed of the bats.

Fun anecdote: Schnitzler became attached to the bats and recalled, "There was one little horseshoe bat that would sometimes fly toward me and land exactly on the tip of my nose to wait to receive food." Yovel had a similar experience. He writes, "When I was training fruit bats to perform a similar task nearly fifty years later, I had a bat...that would land on my shoulder and wait to receive a piece of banana as a prize for correctly performing the task."

The echolocation section describes many diverse experiments, including studies on how bats avoid obstacles - including arrays of thin wires - in their path. Also mentioned are other animals that use echolocation, and the evolutionary war between bats and insects. Insects evolving mechanisms to thwart bat sonar, and bats learning to compensate.

╰┈➤ Evolution

As a biology undergraduate, Yovel developed an interest in bats. This was cemented in 2001, when Canadian professor Brock Fenton - who traveled around the world teaching a bat course - came to Israel. Yovel took Fenton's class at the desert research station Sde Boker, and participated in a number of research projects.

Sde Boker

Professor Fenton was especially interested in the evolution of bat echolocation, and wondered which came first, flight or echolocation. The 'flight first' theory suggests that the earliest bats would glide between the trees and use their sense of sight to discover and hunt insects and the echolocation only evolved later.

Conversely, the 'echolocation first' theory hypothesizes that the earliest bats used a primitive form of echolocation to detect insects, and started to spring after the bugs, which eventually led to the development of wings and the ability to fly.

Fenton suggested a third idea, called the 'tandem hypothesis.' Fenton thought that since both flight and echolocation require so much energy, they had to evolve together. "To reduce the enormous energy cost of echolocation, bats synchronize their calls with their exhalation, and thus save a lot of energy. The bat's exhalation itself is synchronized with the fluttering of its wings, so that every time the wing flaps down and presses against its chest, the bat can produce a powerful echolocation call with a minimal investment of energy."

This issue is hard to resolve because while it's easy to determine whether a fossilized creature had wings, it's very difficult to know whether it used echolocation.

Scientist Nancy Simmons addressed the dilemma by studying the fossilized ears of bats. The ancient fossil Onychonycteris finneyi (clawed bat), from a bat that lived 52 million years ago, was discovered in 2008. Onychonycteris has a primitive wing structure, and may have alternated between flying and gliding.

Fossil of Onychonycteris finneyi (clawed bat)

Simmons and her colleagues claimed that Onychonycteris did not use echolocation because its cochlea (part of the inner ear) is small in comparison to that of bats that use echolocation, but is similar in size to the ear of fruit bats, which DON'T echolocate. Thus, in Simmons's scenario, bats flew before they echolocated.

Simmons assertion started a firestorm, with Professor Fenton publishing a contrary view. The battle raged on for years, and is not resolved yet. Despite their rivalry, Simmons and Fenton remain good friends.

Fun anecdote: When he was a doctoral student in 2007, Yovel participated in a trip to Mexico, to study cactus echoes. A wheelchair was required to move heavy recording equipment, and Mariana Melcón - a fellow doctoral student - pretended her leg was broken, to get the wheelchair to Mexico.

Mexican long-tongued bat approaching cactus

Among other things, the evolution section discusses theories about the evolution of echolocation, and whether or not all bats have a common ancestor (they do).

╰┈➤ Nature Conservation

Yovel observes that bats' number-one enemy is undoubtedly human beings. Urban development destroys bat habitats; wind turbines kill bats; and bat diseases, which can spread by humans visiting caves, kill bats.

In 2006-2007, Al Hicks - a mammal specialist at New York's Endangered Species Unit - found that 'white-nose syndrome' was killing little brown bats in Howe Caverns.

Bats with white-nose syndrome

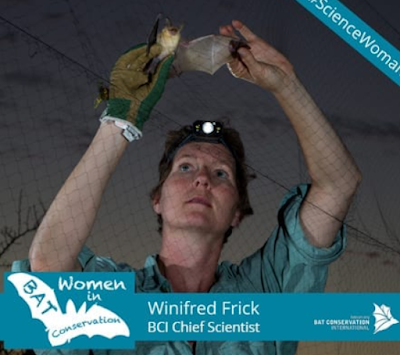

Then in 2009, bat researchers Winifred Frick and Tom Kunz traveled through New Hampshire and found that former bat colonies were empty everywhere, destroyed by white-nose syndrome. The scientists predicted that bat populations hit by the disease would shrink by about 99% in the next few decades if no remedial steps were taken.

The fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, which probably originated in Europe, causes white-nose syndrome. It's possible that P. destructans spores landed in the U.S. on the clothing of someone who had visited caves in Europe, and then visited Howe Caverns. Alternatively, a stowaway bat carrying the spores might have arrived in the belly of a commercial ship.

Government authorities in the U.S. have tried to stem the spread of white-nose syndrome by prohibiting people from entering some caves; having fungicides sprayed in some caves; and killing off sick bats, to prevent the spread of infection. All these measures failed, and the illness has spread all the way to Washington state and California.

Frick is now the director of conservation science at Bat Conservation International (BCI), which has a research team studying white-nose syndrome. At this time, there's no effective weapon against P. destructans. Frick thinks the most promising approach is to try to find ways to help bats survive in regions where the fungus has spread.

Fun anecdote: In 2015, Yovel's assistance was requested for a legal matter. An Israeli homeowner ("D") had a large neem tree, full of yellow-orange fruit. Egyptian fruit bats were visiting the tree, and pooping on the house of D's neighbor ("C"). C wanted D to cut down the tree, and filed a lawsuit. Both C and D wanted Yovel to support them in court. The neighbors eventually agreed to cut down the neem tree and plant a different species.

Neem tree and fruit

The Nature Conservation section also addresses bat destruction by people who believe bats spread rabies. The world's most famous bat conservationist, Merlin Tuttle, is working hard to correct this mistaken notion.

I found the book very interesting and informative and highly recommend it.

Thanks to Netgalley, Yossi Yovel, and St. Martin's Press for an ARC of the book.

Rating: 4 stars

No comments:

Post a Comment