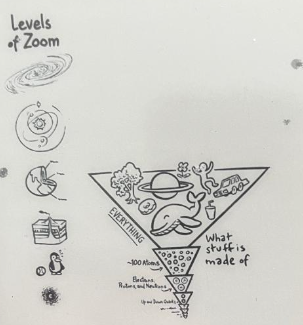

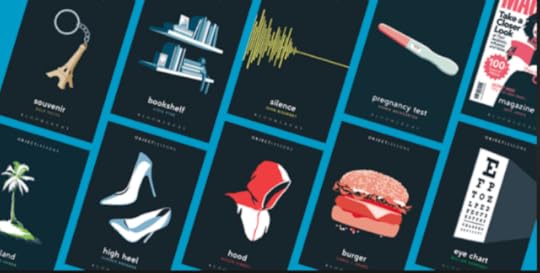

'Object Lessons' is a series about ordinary objects. The narratives are "filled with fascinating details....and make the everyday world come to life." The series has covered many common items, such as golf balls; bread; socks; eye charts; high heels; remote controls; magnets; pubs; trench coats; blue jeans; and lots more.

I was curious about Object Lessons, and though I'm not a musician, decided to read 'Metronome'. The metronome is 'a device that produces a regular sound or motion to help with timing and tempo in music and other activities'. The metronome was invented by Johann Nepomuk Maelzel in 1815, for the improvement of musical performance.

Johann Nepomuk Maelzel

Antique Maelzel Metronome

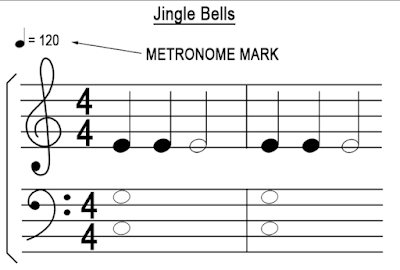

Users could adjust the Maelzel metronome to swing at a specific number of beats per minutes (bpm), from 40 bpm to 208 bpm, and the device produced a steady ticking sound to mark the chosen tempo. Users then assigned a given note value to the objective rate, for instance, quarter note = 60 bpm.

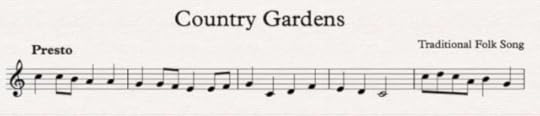

This exactitude was more specific than tempo markings described in words, such as: andante - walking pace; allegro - lively and fast; presto - very fast.

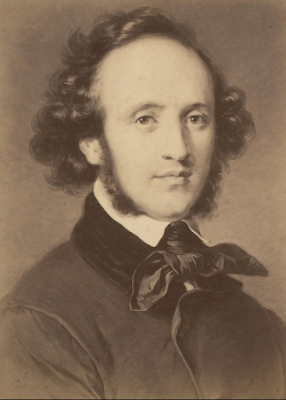

Like anything new, the metronome wasn't immediately popular, and many musicians stuck to their traditional ways. Birkhold details much of the historical controversy over the metronome. For instance, Felix Mendolssohn reportedly asked, "What on earth is the point of a metronome? Any musician who cannot guess at the tempo of a piece just by looking at it is a duffer."

Felix Mendolssohn

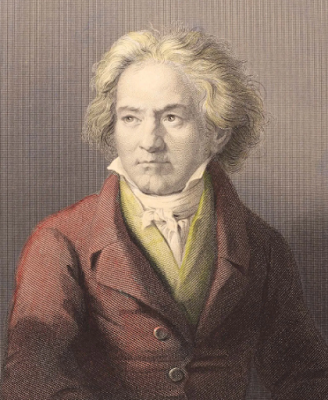

Conversely, Ludwig van Beethoven championed the device. In 1817, Beethoven published a table of tempi for each of his then eight symphonies in accordance with Maelzel's metronome.

Ludwig van Beethoven

The controversy was intense because many musicians preferred their own artistic instincts to the metronome's dictatorship. However, the metronome caught on and "it has firmly rooted itself in our lives and purports to exercise absolute authority over time".

Birkhold explains how composers mark their compositions with metronome marks delineated as MM (for Maelzel's Metronome) to indicate tempo, and how conductors and musicians use the MM marks. The author cites numerous examples of historic and current composers, conductors, and players, which should interest music aficionados.

Conductor Leonard Bernstein

Interestingly, metronomes are sometimes made part of the music, as in 'Poème symphonique' by György Ligeti.

Poème symphonique performance at the Buffalo Arts Festival (1965)

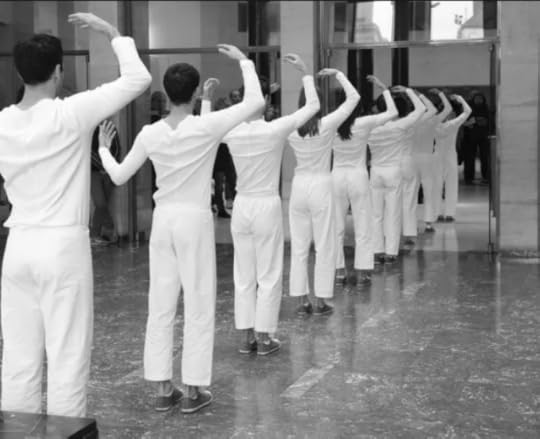

Choreographer Trisha Brown even incorporated the metronome into some of her dances. As an illustration, in Brown's 'Figure 8', eight dancers move to the sound of a ticking metronome.

Trisha Brown's 'Figure 8' dance

Though metronomes are probably best known for their associations with music, they're now used in a variety of other disciplines, such as:

➤ typewriting schools - to improve speed

➤ factories - to train assembly line workers

➤ psychotherapy - to treat people with ADHD, PTSD, and traumatic brain injuries

➤ physical therapy - to assist the gait of patients

➤ sports - to improve golf swings, basketball shots, baseball pitches, and for football practice

➤ acting - to improve/rehearse speech and actions

.......and more.

The world's largest metronome is even a work of art, standing in Letná Park in Prague.

Prague Metronome

Of course, modern metronomes no longer look like the object Maelzel designed. Over the years, Maelzel's wind-up metronome morphed into electric devices, battery-powered devices, and today most metronomes exist on smartphones.

Dr. Beat Metronome by Boss

After numerous engaging anecdotes about metronomes, Burkhold winds up with an inspirational story about the Siege of Leningrad from 1941 to 1944. "After the threat of air raids subsided in early 1942, the metronome transformed from an important warning device to a social connector. Rather than letting silence fill the airwaves between scheduled broadcasts, radio operators played the sound of a metronome. Even in their cold apartments, city residents could hold on to the sound of the metronome. They were survivors. They were united."

German troops on the outskirts of Leningrad

I found the book informative and interesting, and highly recommend it, especially to music lovers.

A Symphony Orchestra

Thanks to Netgalley, Matthew H. Birkhold, and Bloomsbury Academic for an ARC of the book.

Rating: 4 stars