IIn this fun and informative book, particle physicist Daniel Whiteson and cartoonist Andy Warner speculate about aliens visiting Earth.

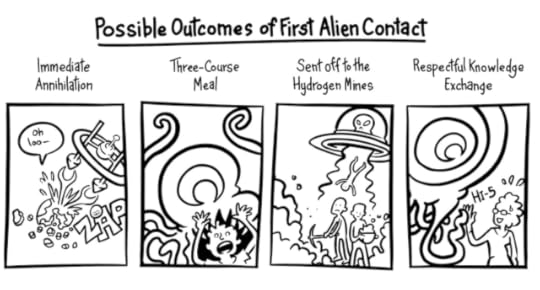

There are various scenarios for what might happen if an alien spacecraft touches down on Earth. On the one hand, snarling tentacled monsters might overrun Earth's measly defenses and fry us into human crisps by a planetwide death ray.

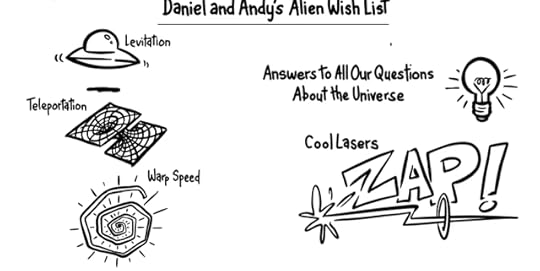

On the other hand, the aliens might come bearing gifts. They've traveled far to get here, using advanced technology, and might be willing to share. The authors speculate, "What if they could just tell us how everything works, so we don't have to blindly hack away for decades or centuries to gain this elusive knowledge?"

Many scientists, especially physicists, believe this could happen. They imagine that physics describes everything in the Universe, not just life on Earth, and so should form the foundation of alien science. Therefore, we should be able to use physics as a mental bridge between ourselves and the aliens.

Whiteson and Warner suggest this view may be too optimistic. They think it's possible alien minds, and ideas about physics and math, are "so different from ours that asking how they do math is like asking what color Tuesday is." The authors speculate that aliens might be so unlike us, there could never be useful communication. For instance, life on Earth is based on carbon and water, but aliens might be made of silicon and ammonia.

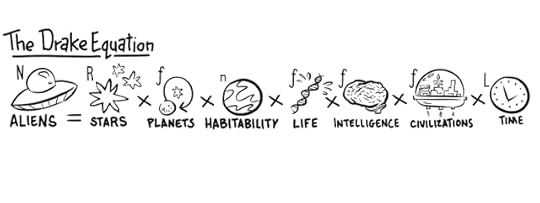

In any case, for humans to interact with aliens, many conditions must be fulfilled. Astronomer Frank Drake devised an equation to estimate the number of alien civilizations we might be able to communicate with by laying out the individual requirements piece by piece. Briefly, the Drake equation includes approximating the number of stars with habitable planets that could sustain intelligent life, and how long they've been broadcasting signals we might receive.

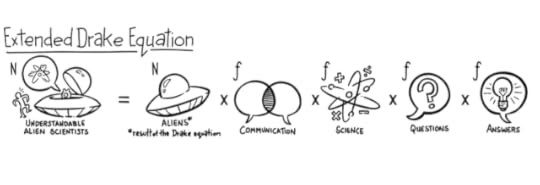

Whiteson and Warner devised an extended Drake equation that summarizes the concept of humans meeting - and learning from - aliens as follows:

The authors go on to discuss our hypothetical 'first contact' with aliens, whether or not they have knowledge to impart. I'll give a brief peek at the subjects covered, and encourage interested humans (or aliens) to read the book.

➤ Do aliens do science?

Though traveling through space would seem to require scientific knowledge, aliens might hit on the technology without knowing how it worked.

For instance, centuries ago, people learned to forge swords and bake bread without understanding the science. Humans WANTED to comprehend though, and they told stories, asked questions, and made observations until they figured it out.

Would aliens have the same desire to understand the universe as humanity? If so, they might have things to teach us.

➤ Could we communicate with aliens?

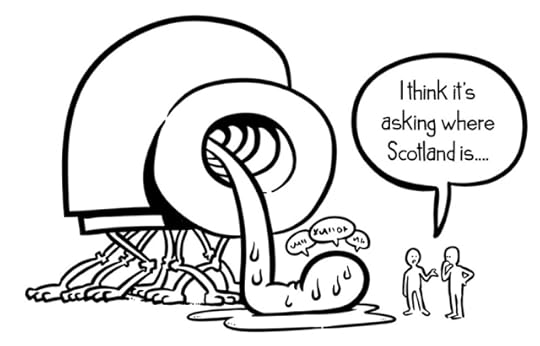

To learn the secrets of black holes from aliens, we'll have to figure out how to communicate in the first place.

The authors note, "Alien language might employ not only unfamiliar words and sounds, but also lights, gestures, or smells - not to mention that the thoughts an alien language expresses may themselves be unfathomable."

As it happens, scientists have already thought about communicating with aliens:

The 17th century Austrian astronomer Joseph von Littrow had a plan to write huge mathematical equations on the Earth's surface by digging trenches in the Sahara Desert, filling them with kerosene, and setting them on fire in hopes that Martian mathematicians would see them.

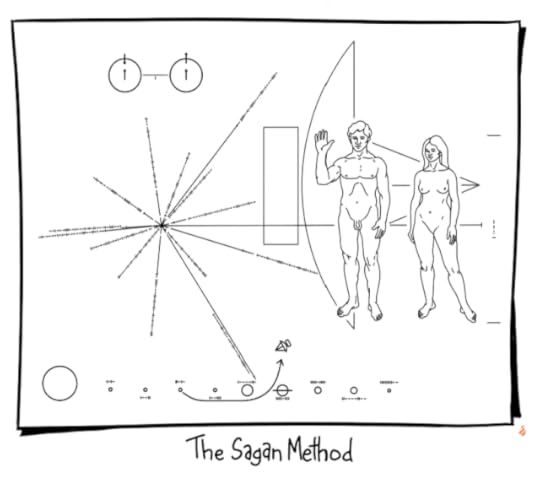

More recently, Carl Sagan designed a message that would be inscribed on plaques attached to the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecrafts, launched in the early 1970s. This is it:

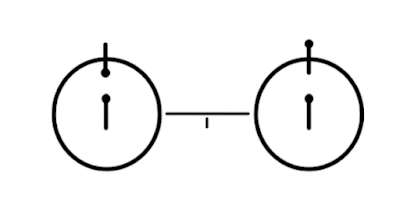

Referring to the first part of the plaque, Whiteson and Warner joke about what an alien might make of it: "All tadpoles must enter the hot tub on the left and exit on the right."

Joking aside, Sagan hoped aliens would recognize it as a depiction of the hydrogen atom. In reality, even other HUMAN physics graduate students struggle with this picture, so it's hard to imagine aliens understanding it.

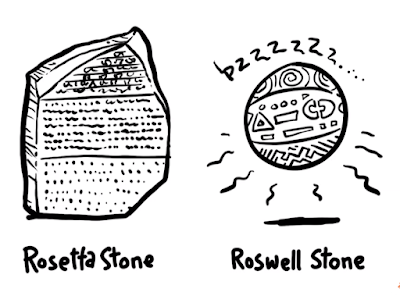

Conversely, humans would probably find it almost impossible to decipher something written in an alien language. It took about a thousand years for scholars to interpret Egyptian hieroglyphics, a HUMAN language, and they needed a cheat sheet, the Rosetta stone - a decree issued in hieroglyphics and ancient Greek - to do it.

The authors write, "If alien minds have very alien ideas, it may be impossible to decode their written language, requiring us to somehow translate a set of unknown words or symbols into a potentially unfamiliar set of concepts." However, if the aliens came here to Earth, then having human and alien brains together might advance communication.

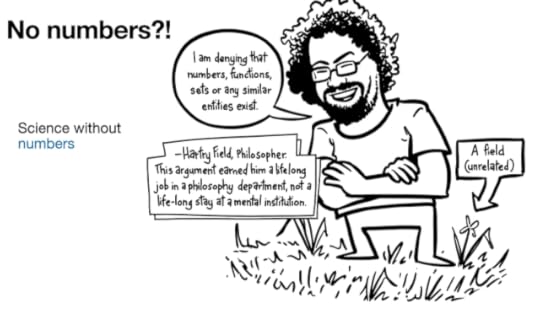

➤ Do aliens do math?

Math is the language of physics on Earth, but can we count on math to be the foundation of alien science. If so, we have a good chance at being able to share information about the universe.

The authors present a long discourse on math, and point out that the most basic math is counting and adding. To illustrate how OUR math might not align with alien math, they present an example: If you put a piece of paper and a pencil on a table and ask an American, 'how many things are there?', they will say 'two.'

If you ask a Japanese person in Japanese, their answer will translate to 'one flat thing, one long cylinder.'

Whiteson and Warner observe that a difference between human and alien perception of math won't matter IF math is a deeply seated element of the Universe, something discovered rather than invented. Contrariwise, "many philosophers worry that math is just part of the way we think, a complex human game like checkers."

➤ What about alien perception?

Even if aliens are mathematical, scientific, and communicative, they may not be seeing the same Universe as us. Whiteson and Warner write, "If aliens have different senses, they will perceive different bits of the Universe - which will naturally lead them to ask different questions about it."

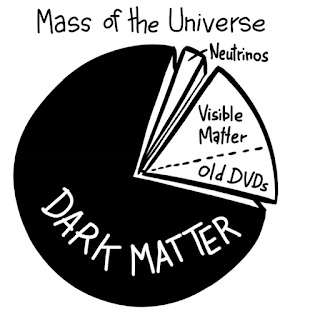

To give an example, aliens may 'see' the zillions of neutrinos passing through everything on Earth (including you) every second. Human eyes are constructed to absorb photons, not neutrinos. In fact, humans can't see most of what makes up the Universe - dark matter. Whatever this dark stuff is, "it isn't just out there in deep space; it's here with us. It's in your room with you right now."

Humans can't see, smell, touch, hear, or sense dark matter. If aliens can, they might have a vastly different picture of the universe than we do. Aliens may even have an alternate understanding of space and time.

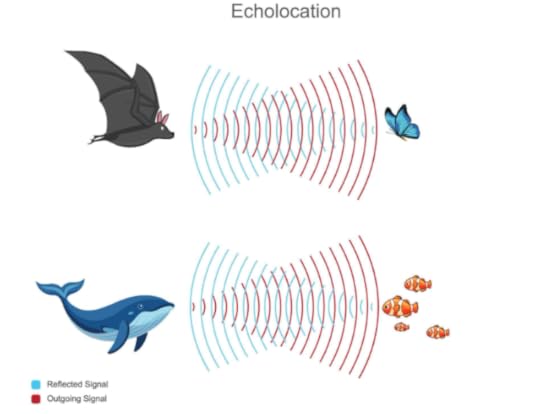

To illustrate the array of senses humans DON'T have, we need only look at other inhabitants of Earth. Some fish can sense electric fields; some birds can sense Earth's magnetic field; bats and dolphins use echolocation; and some cold-blooded animals have infrared vision.

The authors point out that human senses evolved in an Earth environment, and if aliens evolved in a completely different habitat, their senses may also be very different.

➤ What questions do aliens ask?

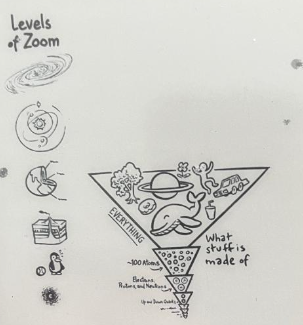

Humans are curious about everything, but (normally) only see the 'big picture.' At a tennis match, for instance, humans can observe the ball going back and forth, but not the atoms in the ball. This works for big things like planets and tennis balls because we can zoom out to determine how the objects move without referring to the atoms they're made of.

More than that, big pictures can bury details, so we zoom the other way to find the smallest objects. The world is made of tiny atoms, which in turn are composed of electrons, protons, and neutrons. Protons and neutrons, in turn, are made of quarks. Particle physicists on Earth study these miniscule entities, but would aliens also be curious about them?

Would aliens see the universe the same way? Would they notice the same things and ask the same questions? Humans live on the surface of a planet and look up into the sky, so astronomy was the gateway science for early humans. If aliens live underground, though, "they may think that focusing on orbits over what's inside is burying the lede. What's reasonable to us may be more cultural than universal."

The authors include an extensive discussion of how and why humans do science, and emphasize that our scientific knowledge didn't accrue by a 'straight path up the physics mountain', but rather by zigs and zags and branches and chance and luck. They ask, "Are aliens on the same route as us, probably further along, or are they climbing a completely different face?"

I guess we'll have to meet some aliens to know. 😊

In sci-fi movies and television shows, humans communicate with aliens rather easily, maybe using a 'universal translator.' Whiteson and Warner make it clear this is an unlikely notion. The book is fun, and the cartoons are hilarious, but it's real science, not a fluffy read (in case you need to know).

I enjoyed the book and highly recommend it.

Thanks to Netgalley, Daniel Whiteson and Andy Warner, and W. W. Norton & Company for an ARC of the book.

Rating: 4 stars

No comments:

Post a Comment